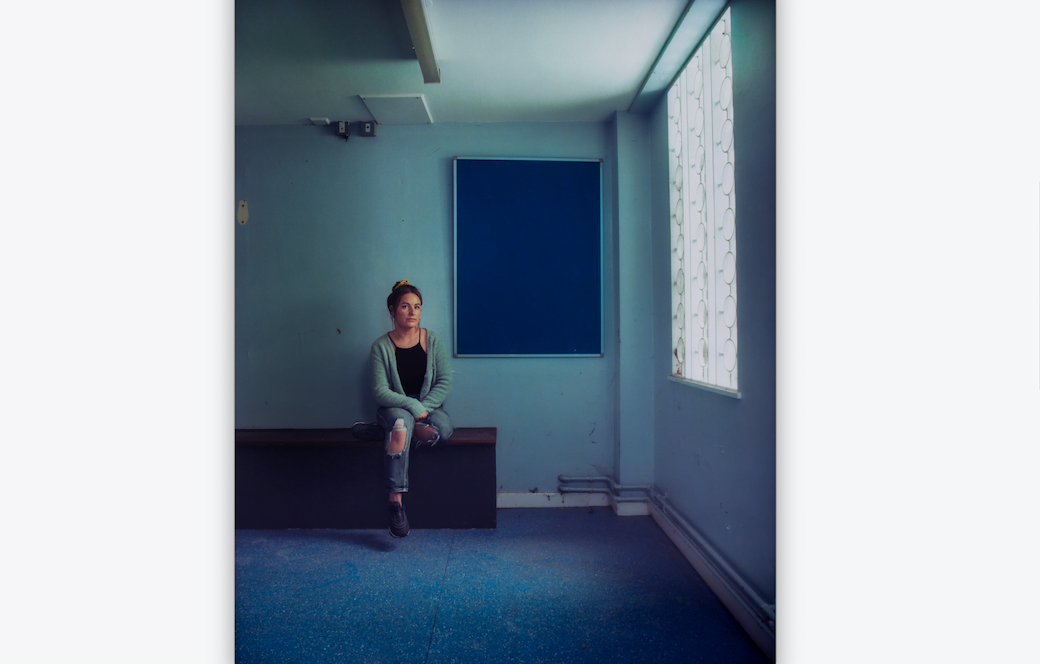

Layers: Looking Inside Holloway Prison is a photographic exhibition where the words are more important than the images they accompany. The photos, by Joya Berrow, are of former inmates of the notorious women’s jail taking one last look at its dilapidated interior before the bulldozers roll in and raze it to the ground forever; the words are by the inmates themselves, writes Michael Holland.

But these are not the usual ex-offenders that you see portrayed in the right-wing press or lined up on low-budget reality TV shows to confirm the narrative set by those with their own agenda on working-class people made to appear happy to be caught up in a revolving door of benefits and bang-up. These women are that special kind that push back against a system designed to retain a status quo, where ‘rehabilitation’ is merely a buzzword and rarely something practised.

Layers allows the viewer to peel away the misconceptions they may arrive with and, through the letters that each woman has placed by their photo, see beneath the fake façade prisoners have to put on to survive, because in those letters is the truth. In those very personal words are the reasons why those women ended up in prison. Right there in the text is a lifetime of domestic violence, alcoholism, addiction, dysfunctional surroundings and a disturbing number who went through the ‘care’ system. It was that system where Beryl, aged 13, was groomed and handed over to her abuser.

The 29 women and transgender Danny – now an award-winning male boxer – were taken back to where they are once imprisoned and spoke their letters, their words, to camera, so that the video could be played at the exhibition and give it another aura of authenticity. So that you could look at their image in a photo, read the words they had written, and see them staring down a camera lens saying those words. That is when you have to think about how you may have judged these people but never judged the system and the society that put them in jail.

Tia writes of her hatred for a father that beat her and left her physically and mentally damaged; a father she can never forgive. Reading Tia’s letter is when the viewer should try to put themselves in a position where they felt a need to write that and proclaim it to the world in a public exhibition. And when you release that you can’t imagine that being a reality, you have to peel off another layer and look at yourself and ask what your role is in this society and system, and how you can change it.

Lucy writes, in verse, an ode to the building that she was once imprisoned by; asking: ‘Where are you now? Consigned to a landfill?’

Katy ponders on the prison staff trained in opening doors and locking cells securely but completely unprepared and ill-equipped to ‘have the knowledge, understanding and empathy’ to support those women who needed more than being continually unlocked and locked up.

Some of the women wrote to their mums, both here and passed; to their younger selves; thank you letters to Holloway being a safe place for them to recover; to family members who looked after their children; letters of deepest apology: ‘I just want to apologise for all the trauma I put you and mother through, writes Nancy. Some even write to a god they found in jail. Nuala writes to her addiction, telling it that she is ready to fight the next battle… Emily writes to her daughter as a warning not to make the same mistakes, but offering hope that ‘anything is possible’. Latoyah marks significant days: ‘July 2009. Found guilty… The scream you released on sentencing – rang in the court room… 2013, starting the resettlement journey, on D-Wing with an ensuite room and key to your door… 31.12.2011. Your first community visit …December 2013 – Your release date… 2015, the end of your undergraduate studies and your graduation year… 2018, Another graduation – but this was for a Masters degree’.

Among the 30 portraits, you will find former prisoners who have gone on to become mums, CEOs, boxers, funeral directors and more. And so it goes on. And that is what Layers is about; women who had endured years of misery before they even went to jail but then set their hearts and minds on never going back.

I will leave the last word to Sara: ‘They can lock the locks, but they can’t stop the clocks!’

Layers: Looking Inside Holloway Prison has been made possible by Power Play Productions and The Daddyless Daughters Project.

Do not go just to look at the photos, go to learn.

Copeland Gallery, 133 Copeland Rd, Peckham, SE15 3SN until 12th March.

Thursday 9 March 11am- 8pm; Friday 10 March 11am -8pm; Saturday 11 March 10am-5pm; Sunday 12 March 11am -5pm

Admission: Free. Book tickets: https://www.copelandpark.com/events/

Daddyless Daughters was founded by former HMP Holloway prisoner Aliyah Ali. Daddyless Daughters provides physical and emotional safe spaces for vulnerable girls and young women who may have been affected by family breakdown, abuse and adversity. They focus on social and emotional development of girls and young women between the ages of 14 – 30 years old, providing physical and emotional safe spaces for them to explore their thoughts, feelings and experiences.

Power Play Productions is led by Polly Creed and Sophie Compton, and tells women’s stories of social justice across multiple mediums, including film, theatre and fine art. Our productions have won awards including a Fringe First. Our impact work has brought international recognition to social issues and tangible change in UK law and policy.