Over the past couple of weeks I’ve written articles about various steam road vehicles which passed through or originated in Greenwich and the surrounding area, writes historian Mary Mills…

Some of these were for individual transport and others were for a number of people and both were based on the sort of horse-drawn vehicle which was available at the time.

There were some attempts at setting up a public transport service based on these vehicles.

https://southwarknews.co.uk/greenwich-weekender/making-merry-merryweather-sons-steam-powered-trams/

Although some of the ‘carriages’ could undertake considerable distances they all had problems which made then impractical for daily use – including water and coal supplies and suitable road surfaces.

In addition there was some hostility from bodies which maintained roads because it was perceived they caused damage.

It is thus difficult to find any which were made after the 1860s and most schemes had ended before 1850. So there is a big gap in time until we get to the next Greenwich based powered vehicle manufacturer.

There were a couple of big firms in Greenwich which produced powered road vehicles in the late 19th century and early 20th century and some experimental works.

This week I want to look at what was eventually an unsuccessful attempt to produce viable road vehicles in the last few years of what had been a major manufacturing company.

I have written before about Penn’s engineering works on Blackheath Road. They were on the site which is now generally called ‘Wickes’.

The first John Penn had opened the works in 1799 to make agricultural equipment. His son was to turn the works into a premier manufacturer of marine steam engines and similar equipment with a worldwide reputation for excellence.

By the 1890s however the firm had begun to lose money, although orders were still coming in. In 1899 they were amalgamated / taken over by Thames Ironworks.

Thames Ironworks was also a major engineering company which was now losing ground to companies in the North and Scotland which could produce the same ships at lower prices because of lower wages.

Like Penn’s it had had an international reputation for excellence. It was based at the mouth of Bow Creek – directly opposite what is now the site of the Millennium Village.

Since the 1870s Thames Ironworks had been in the hands of Hills family. Every book which I have written in the past sixteen years has included a chapter on Frank Hills – commonly known as ‘the Deptford chemist’ but with an important works in East Greenwich and much else.

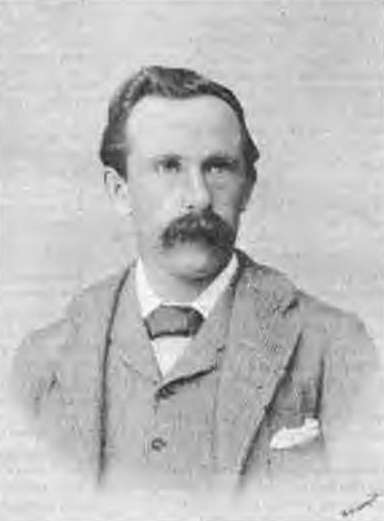

He chaired Thames Ironworks from 1870 but had died in 1892. It was a family misfortune that Frank’s two eldest sons died shortly after and his third son, Arnold, became Chair of Thames Ironworks until the company collapsed in 1912.

Arnold is well-known as the founder of West Ham Football club he was in many ways an unlikely figure to be found as a major industrialist.

He was a temperance and vegetarianism advocate who believed in ‘fellowship schemes’ between management and workers. Thus he was the exact opposite of his unscrupulous father.

Traditional work on both steam engines and warships was now limited and would soon be no longer relevant.

What contracts there were now going to the Tyne or Clyde where wages were lower. However at Blackheath Road engines continued to be made, and warships were still ordered.

But it was clear that in order to survive the company needed to diversify.

Initially some of the Greenwich site was used for a new boiler works for the French Belleville company; there was also a steam driven electricity generator which led to much restructuring of the plant.

West Kent Argus reported that the ‘new shops for engine and Belleville boiler work were probably the best of their kind in the United Kingdom’.

William Penn, the last member of the family to run the company resigned in 1901.

Other companies throughout the country were beginning to manufacture road transport vehicles and Thames management must have seen this as a possible solution to the decline in the traditional manufactures.

A lorry was designed and a prototype made. This was said to be ‘identical in all respects with the vehicle which ran in the recent Commercial Vehicle Trials of the R.A.C’.

It had a four-cylinder engine, and there was an exceptionally large radiator, which… has given the whole vehicle a rather heavy appearance. There was also a 15-cwt.petrol powered van ‘a serviceable-looking machine, fitted with a canvas tilt’.

These were shown at the Olympia Motor Exhibition in 1905. Soon after a new factory was built for what was to be called Thames Engineering Works.

It was at the lower end of the Greenwich site and equipped with modern machine tools. The engines for these vehicles were built in Greenwich while the bodywork was done elsewhere and Thames also set up a West End agency to handle sales.

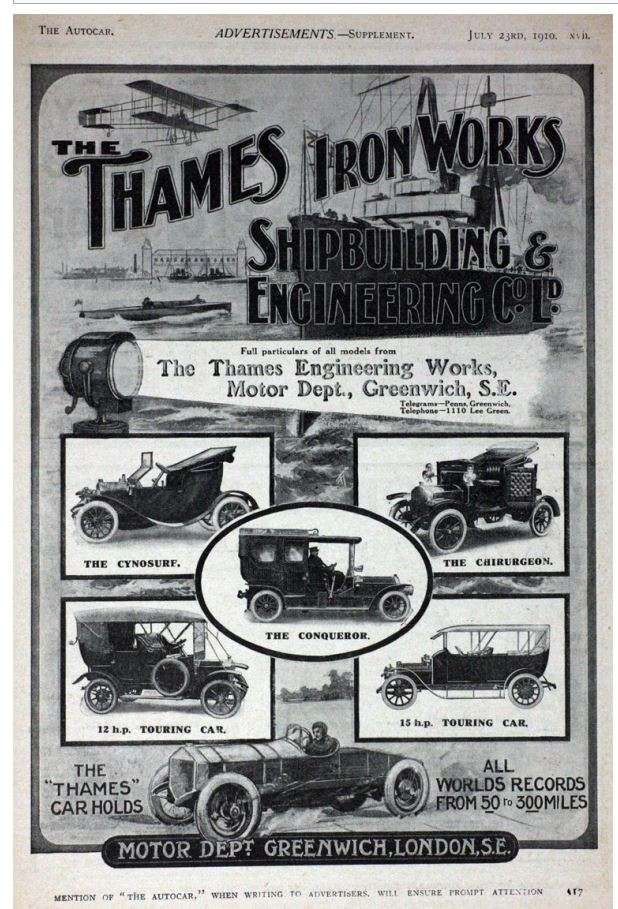

They continued to exhibit at successive Olympia motor shows what was called the ‘Thames Range’

A young apprentice employed at the works in this period was Barnes Wallis the future inventor of the

Dambusters’ bouncing bomb. He remembered working on an early London taxi cab which was ‘suitable for London traffic, and conforming to the Metropolitan Police requirements ‘and ‘would do quite well for private service or better class hiring work’.

Wallis also remembered working on what he described as the first ever racing car built in England. I don’t know if this claim to be first such car is true and can find no reference in histories of motor racing.

However, in 1907, a newspaper report says that ‘W. T. Clifford-Earp, driving a six cylinder Thames car annexed four world records’ … ‘the 50-mile, mid 100-mile and one and two-hour records, and also established a record for 150 miles’.

In 1909 another report says ‘a new world record’ was set for G.Palmer’s cord tyres by C. M. Smith on a 6 cylinder Thames car at Brooklands …the most severe test to which motor tyres have ever been submitted.’

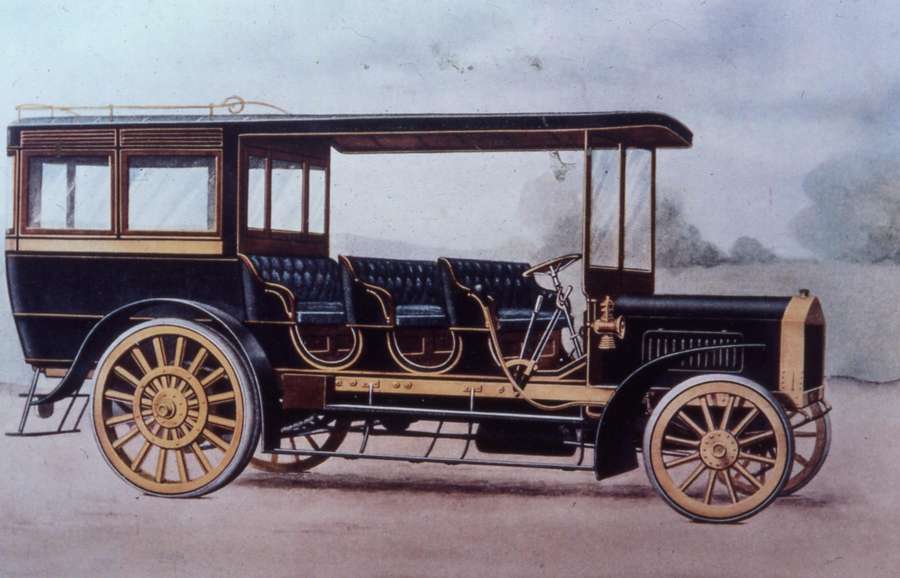

Meanwhile in Folkestone, of all places, in 1905 a Mr. Cann was in need of better vehicles for his London and South Coast Motor Service route between Hythe and Folkestone.

He placed an order with Thames Ironworks, Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, for their experimental motor coach built to seat 20 passengers.

Apparently he liked the large driving wheel, and the six cylinder engine. A new model was delivered in 1906, but there were some initial problems but nevertheless Cann went ahead and ordered five more coaches and even more were added later.

Apparently the use of these vehicles continued on the south coast and coaches in service are seen in photographs credited to the 1920s.

They also provided public service special vehicles. In 1905 members of the Lewisham Borough Council saw a demonstration of a means of destroying waste by a machine called The Clem, which completely pulverized the refuse. There are also reports of vehicles for sprinkling water on streets and no doubt there were other such specialist equipment produced.

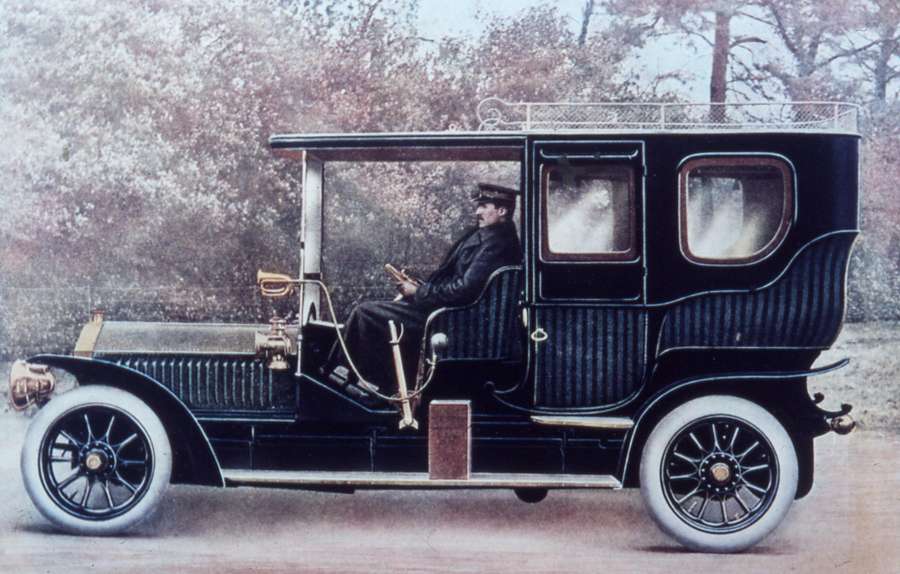

Many years ago I was given some drawings of various elegant motor cars by the late Patrick Hills – Arnold Hills’ grandson. He was very proud of these and said that they were the cars made by his grandfather’s company.

In newspaper reports of Thames Engineering I have only ever found reference to commercial vehicles, lorries buses and some specialist vehicles for local authorities. I don’t really know if these motor cars were ever made.

In 1912 Thames Ironworks, the parent company went into receivership following a stand-off with Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty over the placing of orders in London where wages were high.

There was a great demonstration in Trafalgar Square by 10,000 East Enders protesting at so many skilled shipyard workers being put out of work by the Company’s failure.

I’m sure that there were great aspirations at Thames Engineering to produce efficient and saleable vehicles but what brought Thames Ironworks down was the failure of the shipbuilding business and the determination of government to place orders away from the Thames. The failure of the motors business was just collateral damage.

Strangely there are reports that in 1913 a double-decker coach constructed which resembled a stagecoach without the horse. This strange vehicle is exhibited in a Dutch Museum, and has been widely illustrated.

In May 1913 the Blackheath Road site was put up a sale by auction and was sold to Messrs. Defries, the lighting specialists.

However it is said ‘nothing came of the project’ and, sadly there are soon reports of problems of a financial and probity nature.