The tagline that Tate Britain gives its Rossettis’ retrospective is ‘Radical Romantics’. As we wandered into the 7th room, all romance had departed as my friend looked at the umpteenth puffy-haired, pouting goddess and exclaimed ‘Not another one!’, writes Madeleine Kelly…

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where the exhibition went wrong because there are so few moments it went right.

In the first room, the sight of a young Christina Rossetti as the Virgin Mary curled up on the edge of a low bed, glaring at the Angel Gabriel’s gift is a psychologically intense take on the theme. This version of ‘The Annunciation’ by Dante Gabriel Rossetti is accompanied by his sister Christina’s poetry on the walls. Standing at various fixed points in the room, you can hear the poems read aloud. Poetry in an art exhibition is a tricky task to pull off, but the Tate does an admirable job here.

If the first room makes a case for ‘The Rossettis’ as a revolutionary family group, the next 8 rooms largely forget about the contributions of the rest of the family to focus on Dante Gabriel Rossetti. It is his life and loves that the exhibition pores over, at pains to find him a radical romantic.

In truth, Dante nods to revolutionary ideas more than makes them. His split from the style of the Royal Academy with the establishment of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood is rendered as teenage insolence in his cartoons. Of the Brotherhood, it is not Dante but Millais who, even in his short inclusion in this exhibition, stands out. An early sketch of his ‘Christ in the House of His Parents’, depicts the Brotherhood’s revolutionary tackling of modern social issues more than other Pre-Raphaelite paintings of medieval subjects ever could. Based on a real carpenter’s shop in Oxford Street, the sketch humbles our notions of God and dignifies our notions of work.

Rossetti was not as busy championing the working class as he was sleeping with them. The exhibition tastefully calls his relationships ‘unconventional’, but it is believed that his delay in marrying muse Elizabeth Siddal was in large part down to concerns about her lower class. The exhibition tries hard to argue that Siddal was a worthy painter/poet in her own right, but in her inclusion only alongside Rossetti, it fails to prove it. Here her work is exhibited only alongside similar works of her husband’s with commentary almost exclusively on the impact she had on him.

The later ‘revolutionary’ work of the Arts and Crafts movement which Rossetti was a part of, is overshadowed by the gallery’s constant reminders of the ways the movement’s interest in ‘Orientalism’ propagated the view of the East as a mystical and primitive land. A view that encouraged Britain’s continued colonial project. It is fitting that a retrospective aimed at assessing Rosetti’s impact includes these details, but next to images of his work exclusively in upper-middle-class homes, it leaves the man looking more like a sell-out than a radical.

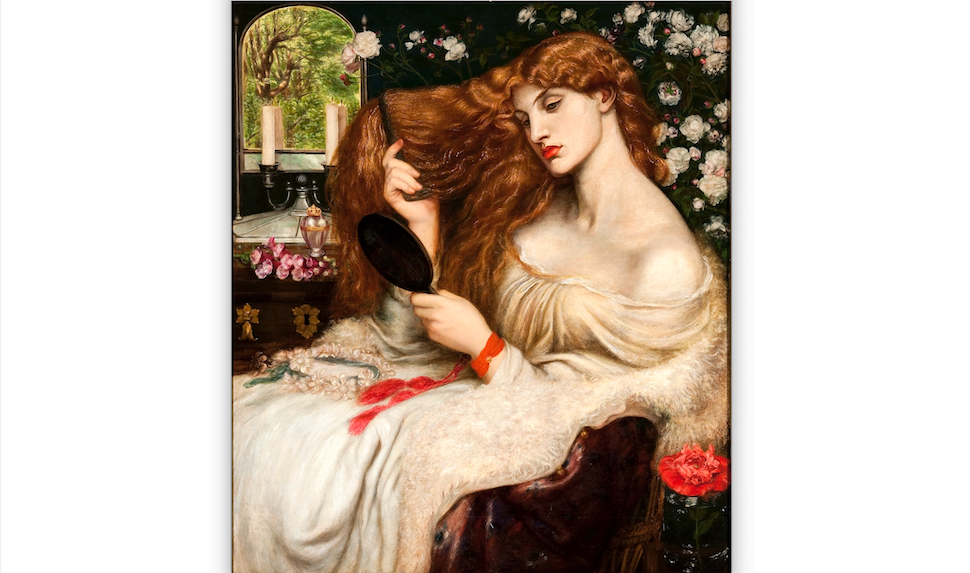

By the end of the exhibition, fatigue sets in. You are treated to portrait after portrait of colourful and stiff femmes fatales too unreal to be sexy which mostly illustrates Dante’s incredible ability to flatten the women he claimed to love into one ubiquitous image. You claw your way to the end, barely stopping to take in the final room desperate to make it out of the so-called revolution and into the sunshine.

Tate Britain, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG until 24th September. Times: Daily 10.00 – 8.00.

Admission: £22, £20.

Booking: www.tate.org.uk