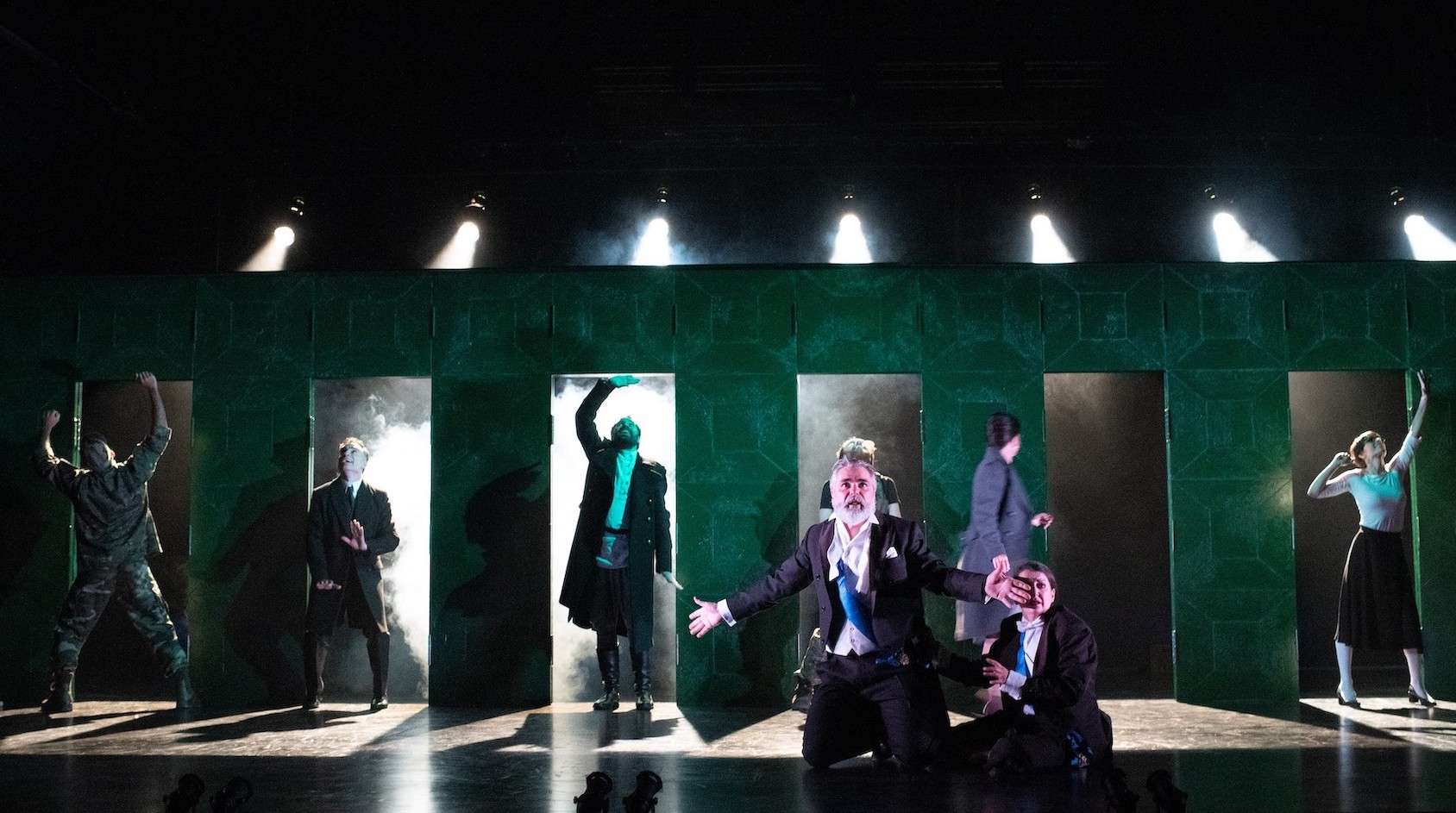

In front of a wall of dark green doors, a man stands alone. For a moment there is silence. Then, manic dance music plays and bodies break out through the doors in various degrees of mania. The eruption ends almost as quickly as it starts and starts again as quickly as it finished. This surreal anxiety dream is Cheek By Jowl’s vision of Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s 1635 play Life is a Dream (La vida es sueño), writes Madeleine Kelly.

The frenzied dreamscape of the play’s beginning leaves the audience’s reality on shaky ground as the play progresses. As people emerge from the doors again as characters, you never trust entirely that they will not disappear again. Eventually, however, even the lone man is adopted somewhat reluctantly into the play’s action.

The play centres around Segismundo, a Polish prince banished to a tower as a child because of a terrible prophecy. Having grown up in darkness, he is called back to the palace by his ageing father who is beginning to doubt the certainty of the oracle. The story whips between forest, prison, and palace just as suddenly as characters emerge and disappear via the doors. The scene changes so often that structures of power and reality become as destabilised in the palace as they have been in the forest.

As the sparse set means that each scene resembles the one before, the landscape of the play becomes more psychic than physical. The play’s characters are frequently made aware of this unreality, two of them even watching one of the scenes play out, popcorn in hand. This surrealism can lower the stakes of the play, turning some of its central questions and plots away from ethical inquiries and into philosophical games.

The body of Segismundo tracks these changes. In the first half of the play, the forgotten prince moves from feral captive to tragic clown, to comic tyrant and back again. Alfredo Noval’s physicality in this role is the beating heart of the play that is sometimes so dizzying the audience begins to detach. Adjusting to the civilised world, he staggers into the audience in awe, stealing our drinks, and clutching our hands. He apes the mannerisms of those on stage, he sees our familiar world through his strange hands. The audience laughs at him, but we also like him. When he turns to revolution it is another strange game to him, a part he puts on for the benefit of his audience.

At times this version gets lost in a psychological maze of its own making but it is at its best when it asks how we should behave in the face of our own absurdity. If life is a dream, is it possible for us to act as our own agents, not turning away from life in fear but moving towards our futures slowly and kindly?