Nineteenth century Greenwich was home to any number of innovative engineers – with a reputation for skilled metal working. Most famous are the armaments made in the Royal Arsenal and the steam engines made at establishments like Penn’s on Blackheath Hill, but also there were many smaller firms. It was also an area where experiments in such devices were sometimes tried out – and this included mechanical road transport devices.

Inventors in the late 18th and early 19th century wanted to apply the developing technologies to road vehicles. One of the earliest and most famous was the working model steam car made by William Murdoch in 1782. Although he was in Cornwall it was described and popularised by Blackheath resident, writer Samuel Smiles. Locally, from the 1820s onwards, some roads were – well, almost – buzzing with newly invented vehicles. Most of them were steam powered and while they were developed as the same time as railway locomotives, they were lighter and smaller and, perhaps, more sophisticated.

The idea of steam road transport had been around a long time. Another early inventor from Cornwall was Richard Trevithick. He came to London in 1803, bringing with him a steam locomotive which he had developed in Cambourne and which had been demonstrated on roads there. The original model was burnt out when Trevithick and his friends were in the pub eating roast goose a couple of days after Christmas. Later he demonstrated locomotives in London – I have seen a replica of his vehicle in Dartford, where he was living at the time of his death.

Deptford, Greenwich and Woolwich were on the main Dover Road and a test for newly developed vehicles might be to ascend Shooters Hill –not only on a main road but steep and well known. Many vehicles which were developed elsewhere were tried and tested here. Inventors needed publicity for their carriages and it was a very good advertisement to be seen taking the new vehicle over a difficult piece of public road, so Shooters Hill was a firm favourite. We need to remember the description of the road up Shooters Hill in Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities – the novel was written in 1859 but set in 1775 – ‘he walked uphill in the mire by the side of the mail as the other passengers did … with drooping heads and tremulous tails [the horses] mashed their way through the thick mud … there was a steaming mist in all the hollows … a clammy and intensely cold mist …. A loaded blunderbuss lay on the top of six or eight loaded horse pistols, deposited on a substratum of cutlasses’.

An early powered vehicle which ascended Shooters Hill seems to have been that built by Samuel Brown. It was, however, not a steam car – and the Samuel Brown involved was not the distinguished Blackheath resident associated with various types of chain manufacture. I must admit to having confused them in past articles, and I’m sorry about that.

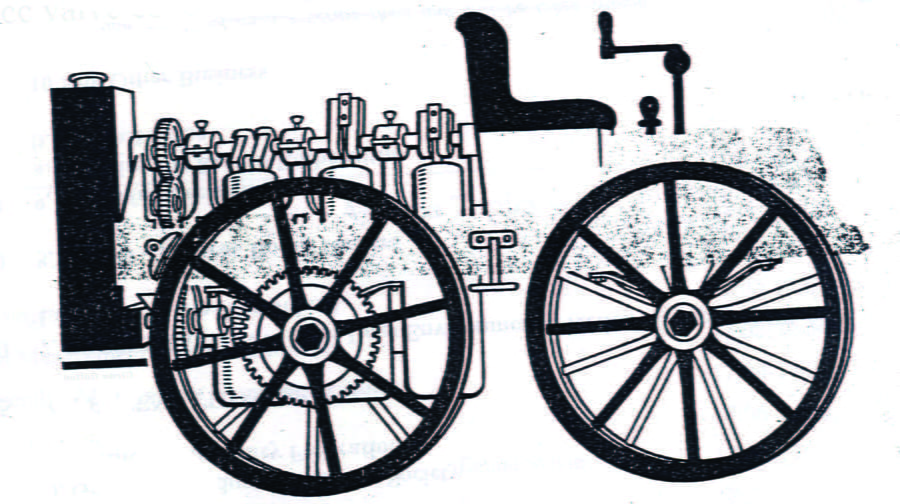

This, other, Samuel Brown was a cooper whose patents included improvements to machinery for manufacturing casks. He lived in West London, in Eagle Lodge in Brompton, between 1825 and 1835, and the road vehicle he developed there was tested by driving it up Shooters Hill on 27th May 1826. It was powered by ‘the first gas engine’ – unlike many later vehicles which climbed the hill it did not use steam but was powered by gas, perhaps coal gas or the vapour from commercial alcohol. The engine was known as a ‘gas vacuum’ and has been claimed as the forerunner of internal combustion. The car itself had four wooden wheels, a small seat for the driver and very little room for anything else on top of a gigantic engine. It climbed up Shooters Hill very slowly but ‘with considerable ease’.

In the 1820s many people thought that Mr. Brown’s carriage and others would never be able to go uphill because of something they called ‘perpendicular resistance’. The drive up Shooters Hill was to disprove this once and for all. Reports said ‘this precipitous surface experiment demonstrated that perpendicular resistance could be surmounted’. Mr. Brown’s car went up the hill all right – and plenty more were to follow it.

There had been concern about the weight of the vehicle and the load it could carry as it went up the hill. However it was reported that seven people sat on the shafts and it ‘appeared to make no difference to the motion’. Then ‘some sailors who were accidentally passing’ surrounded the engine ‘and expressed their amazement at its impelling power’. They ‘put a young chimney sweeper on the board which corresponded to a coach box on an ordinary coach’ and he ‘became the first conductor of a heavily laden vehicle up Shooters Hill without the agency of horses’.

Shooters Hill had recently had a new road surface laid down to help coach wheels get a purchase at the point where these experiments took place. It was also thought that a steam powered vehicle could only be used on a slightly inclined surface. However Mr Brown’s gas powered invention was shown to be able to work on the road in the roughest of conditions. It was also pointed out in reports of the ascent that a steam engine explosion would ‘produce considerable mischief’ but this ‘pneumatic engine would not explode in such a manner’ and ‘there cannot be any scattering expulsion of its fractured parts’.

Brown’s ride up Shooters Hill has been given very little attention in histories of motor transport although it was well reported at the time in the technical and national press. It was very early in the history of powered road transport and, in some ways, isolated from the later development of the internal combustion engine. Clearly it has not been described in histories of steam transport because steam was not used.

After this experimental trip Brown himself seems to have abandoned the idea of using the system for a road vehicle and adapted it to be used for powering boats. The ‘Canal Gas Engine Company’ was formed by a group of entrepreneurs to exploit the engine for use in vessels on the Croydon Canal – the canal which ran from New Cross to Croydon and which became the route of the London Bridge/Norwood Junction railway line. The canal was not a success and the gas engine project floundered with it.

Brown was not the only person in Greenwich trying to put powered vehicles on the roads in the 1820s. Another, more local, inventor was working on a steam carriage. John Hill came from Greenwich. He may have been the John Hill from Creek Street, Deptford but ‘John Hill’ is a common name. His partner in the steam carriage project was a Timothy Burstill who came from Edinburgh and was, of course, a competitor in the 1829 Rainhill Trials for an effective railway locomotive. His entry there was with ‘Perseverance’ – said to have been ‘no more than a glorified domestic boiler’.

In London Burstill and Hill made a very heavy, 8 ton, road steam carriage with a very large boiler. This meant that it was very slow and could only do, at the most, three or five miles an hour. They found it difficult to get passengers because, it emerged, people were scared of sitting close to the enormous boiler and as it turns out, with good reason,

They were quite right to be afraid because this boiler eventually exploded during a demonstration run in Kennington outside ‘New Bedlam’, today that’s the Imperial War Museum. What happened is a good example of what the writers on Brown’s non-steam engine said about the dangers of steam. The carriage was ‘making a short turn, in order to get into the public road, when one of the wheels stuck in a piece of soft ground, the fore wheels being locked at the time, and the steam being generated faster than expended, the boiler burst, with a great explosion’. No one was badly hurt in the accident although two people were taken to hospital. Twenty three people were standing nearby ‘on the bank’ and one man had his foot on the machine itself. Burstill and Hill claimed that the fact that no one was killed showed how safe the engine really was! No more was heard of it.

Such steam carriages were experimental and none of them ever ran a regular public transport service. This changed in the late 1830s when new carriages came on to the roads which were designed to hold fifteen or more passengers and run an ‘omnibus’ service.

The next article will look at them and some of the others.

Getting up Shooter’s Hill under their own steam (or gas)