It was a warm late April’s evening in 1999. The Admiral Duncan pub on Old Compton Street in Soho was filling fast.

Drinkers were keen to kick off the Bank Holiday weekend. Music blared, people got lost in conversation, the bar was getting busy. Everyone was beginning to unwind after work.

Unbeknownst to them, self-confessed neo-Nazi David Copeland had visited the pub and placed a bomb laced with 1,500 nails at the foot of the bar, according to the BBC. At 6.37pm on April 30, the bomb exploded, tearing through the popular Soho bar, killing three and injuring at least 70 people.

Those who died would be later named as John Light, 32, Nick Moore, 31, and Andrea Dykes, 27, who was pregnant at the time.

Copeland, who had carried out attacks on Black and Asian communities in Brixton and Brick Lane earlier in the month, was arrested and sentenced to six life sentences for the heinous attacks.

As the 25th anniversary of the attacks draw near, the Local Democracy Reporting Service (LDRS) spoke to survivors and community members about that horrific day.

‘INCREDIBLE SENSE OF DOOM’

Westminster City councillor Patrick Lilley, 64, ran a gay nightclub in Brixton and worked in Brick Lane at the time. He recalls hearing about the bombing through the radio.

He said: “I had an incredible sense of doom because this heavy dark wave of hate had washed up where I ran my club and where I worked. I noticed being surrounded by this awful situation of terrorist incidents coming closer and closer.”

The West End ward councillor said he was in “total shock” and immediately began to cry. He said the attack felt “very personal”, saying: “Like so many people who have been bullied in their lives, you have a pretty sensitive heart for these sorts of incidents… So many LGBTQ+ people have experienced that.”

He said the attack took place at a time when the gay scene in Soho was thriving. To this day, Patrick still wonders what had been running through Copeland’s head.

Patrick said the bombing only encouraged him to campaign harder for LGBTQ+ rights and was partly behind his decision to go into politics. He is now the LGBTQ+ champion for Westminster City Council.

Patrick said: “It made me the queen I am today and it certainly did instill a sense of duty to help others who have been victims of prejudice.”

Richard Torry, 64, remembers being ordered out of his Old Compton Street flat by police. Richard, who has lived on the busy London street since 1980, said he walked past the pub moments before the explosion.

He said: “I thought it had gone off in Leicester Square because it was so loud. I realised later [the explosion] had echoed off the buildings. I looked out the window and saw people running down Wardour Street. I thought they were running away but they were running towards it.”

He said police had arrived within minutes and began evacuating buildings in case there was a second bomb. Richard hid in the back of his apartment waiting for a sign to leave.

He packed a bag full of clothes and rushed off to a friend’s place, unsure of when he’d be able to return.

He says he can still picture people strewn across the street covered in bloody clothes.

‘I SAW A BRIGHT BLUE LIGHT FLASH’

Gary Fellowes, 65, arrived at the Admiral Duncan around 6pm after finishing work in Whitehall later than usual.

He was meeting friends and sat at the back of the bar when the bomb exploded. He said if a friend hadn’t stopped him for a chat, he would have probably died.

He said: “I was about to go to the bar to get a drink when a friend introduced me to a friend of his and I thought ‘I can’t be rude. Let’s chat for a few minutes before I go and get a drink’. It must have been what saved me because the bomb was at the bar.”

The next thing he remembers is seeing a bright blue light flash. He said: “At first, it sounded like metal hitting the ceiling and then I heard someone say ‘oh s***’. I thought someone had split beer on the jukebox and caused it to smoke up but the next thing I knew was there was this deafening silence and the smell of sulphur.

“There was so much smoke swirling around and that’s when I knew it was a bomb.”

Gary began to worry he may never see his parents again. He eventually stumbled out and made his way up the road to the King’s Arms where staff called an ambulance. He noticed his boots were singed with metal and his shirt was covered in someone else’s blood. He was treated for a burnt hand and face.

Gary would find himself in the Hatfield rail crash 18 months later where he sustained a broken leg.

The 65-year-old, who calls himself a “resilient guy”, said he has been humbled by these events which he said allows him to understand the angst and fear families of loved ones caught in disaster feel.

He’s also no stranger to pushing himself. He became a British Airlines cabin crew member despite being a nervous flyer. He said this helps him connect with other nervous flyers.

He said moments like the 7/7 bombings give him flashbacks and that he keeps an eye on unattended bags and isn’t afraid to “kick off” if they’re not moved.

To this day, Gary refuses to mention Copeland’s name. He said this is to rob the deranged killer of the notoriety he felt Copeland craved from his actions.

It’s a rule fellow survivor Mark Tullett also follows. Mark was also standing at the back of the bar when the bomb exploded. In his book Berwick Street to Barcelona, Mark described thinking a lightbulb had popped and following his partner Tony out of the pub.

The couple would eventually marry and move to Spain in 2004. Tony died of cancer eight years ago.

Mark told the LDRS that Tony was “outed” at work as a result of the bombing. In his book, the 63-year-old said Tony had shows his boss at the Ministry of Defence a newspaper photo of him at the Admiral Duncan to explain why he might be a bit jumpy. His boss asked if a female friend in the photo was his partner.

The passage reads: “Tony told him no, the guy behind was. His boss expressed a little surprise, but no more. Happily, it was the same with all his colleagues.”

Almost 25 years on, Mark says he “very aware” of packages being left out and says he scopes out of place “to make sure there are no threats”.

Every anniversary, he calls Kath, the friend who was at the bar with him that evening. He said: “We have a little chat about it but we prefer to forget about it because some of the memories that night were quite horrific, which is why I don’t want to talk about it, because it gives me panic attacks.”

STRONGER IN THE LONG RUN

Mark Healey runs the anti-hate crime charity 17-24-30 National Hate Crime Awareness Week. The charity holds remembrance services for the bombings every year and has the dates of each bombing in its title: Brixton on April 17, Brick Lane on April 25 and the Admiral Duncan on April 30.

The charity, which he created in 2010, will mark the 25th anniversary of the bombings at each site. To remember victims of the Soho attack, he’s arranged a procession from the pub to St Anne’s Gardens.

For Mark, the anniversary is a chance to stand in solidarity with those affected for “as long as is needed”.

He mentions meeting three men who were drinking nearby when the bombing exploded and who ran home instead of staying. He said: “I would tell them what they did was normal. You were in a fight or flight mode and it’s ok to run away.”

As a victim of homophobic attacks himself, Mark says it’s important to steer the conversation about hate crimes. He said: “There is initial shock and horror and outrage but then there’s a desperate need to turn something bad into something good for the community.”

He added: “The biggest deterrent [for terrorists] is knowing they will make our community stronger in the long run.”

Copeland’s terror resulted in the deaths of three people and injured 139 more. He was arrested shortly after the bombing and sentenced for six life sentences in 2000 for three counts of murder and three counts of causing explosions in London in order to endanger life.

Copeland would go on to admit the killings. When police raided Copeland’s home, they found a Nazi flag hanging on his bedroom wall along with clippings of the newspaper coverage of his attacks.

Photos:

Mark Tullett, 63, now lives in Spain. Credit: Mark Tullett.

Mark Healey outside the Admiral Duncan on April 8, 2024. Mark runs the National anti-hate crime charity 17-24-30 National Hate Crime Awareness Week.

Gary Fellowes outside the Admiral Duncan on April 8, 2024. Gary was drinking in the Admiral Duncan when the bomb went off.

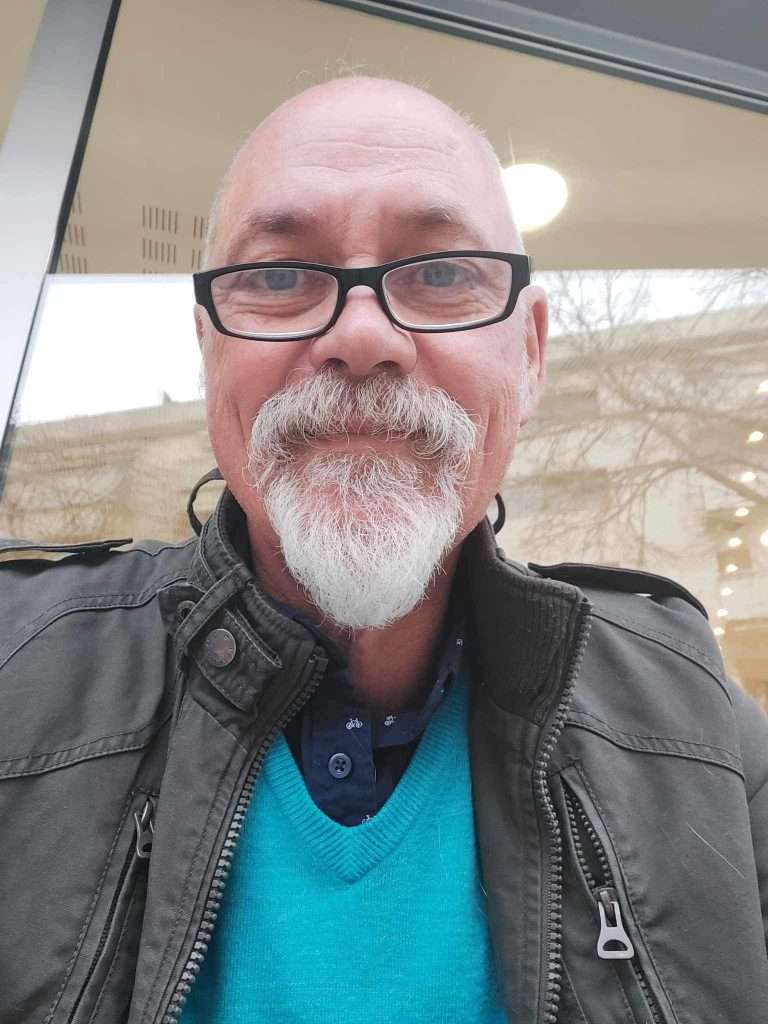

Westminster City councillor Patrick Lilley, 64, outside the Admiral Duncan on April 8, 2024. Patrick said the attack felt ‘very personal’.

Richard Torry, 64, outside the Admiral Duncan on April 8, 2024. Richard lives across the road and said he was forced to evacuate from his flat on the day of the bombings in 1999. Credits: Adrian Zorzut.

Dozens were injured in the first explosion outside a Brixton supermarket