In the past five articles I’ve been talking about manufacturers and experimenters with mechanically driven road transport in Greenwich in the 19th century, writes historian Mary Mills.

The majority of these vehicles were steam powered and most seem to have replicated private coaches and carriages with some experiments with making public service vehicles.

Last week looked at early 20th century attempts to build commercial vehicles and public service vehicles at what had been Penn’s works in Blackheath Road.

https://southwarknews.co.uk/history/a-history-of-penns-engineering-works-and-the-early-vehicles-made-in-blackheath-road/

This week I need to return to the 19th century and look at a firm which, rather surprisingly, was making engines for public service vehicles at quite an early date.

We all know Merryweather’s as a manufacturer of fire engines. However their fire pumps were carried on horse-drawn vehicles until the 1890s while from the 1870s they made steam powered trams.

Their first tram engine was actually made in Clapham before they moved to Greenwich in 1876.

In 1872 a Croydon-based engineer, John Grantham, had designed a steam tram: it was a four-wheel double deck car with a two cylinder engine.

The prototype was built by the Oldbury Railway Carriage and Wagon Company while the steam engine which powered it was supplied by Merryweather & Sons.

After some problems, including modifications to the engine, it went to the Wantage Tramway which took passengers between the town and the station.

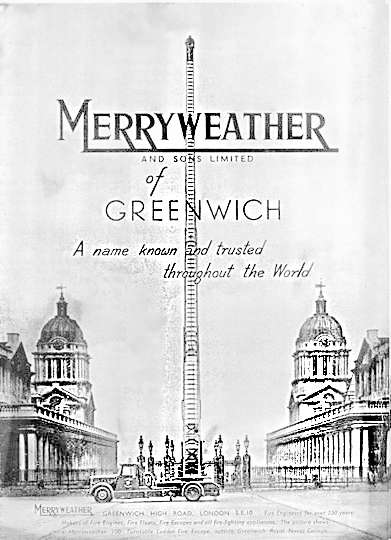

Merryweather’s moved to Greenwich in 1876. Many people will remember their works in Greenwich High Road and today new buildings stand in what is now called Merryweather Place.

It had a long Art Deco frontage but despite strong protests about its demolition and a lot of very hard work by local peopletry and save this, and get older parts of the factory listed, because it had been rebuilt following Second World War bombing it could not be listed and saved.

Having moved to Greenwich in 1856 Merryweather’s continued to make trams – I assume they made the bodywork as well as the engine although that is a bit unclear.

Most of these vehicles were sold abroad. Between 1875 and 1892 the factory produced about 174 steam tram engines, of which only 41 were used in Britain –they included 46 for Paris, six for Kassel Germany, fifteen for Barcelona, fifteen for the Netherlands, eleven for New Zealand and fifteen for Rangoon.

One of the problems for using steam trams in England were the rules and regulations and the need to apply for and get permission from the Board of Trade.

There was also what we now call ‘the Red Flag Act’ – where steam vehicles on public roads were limited to very low speeds and had to have a man walking from with a red flag.

This had originally been passed after complaints from the Turnpike road authorities and others who had to maintain roads, about the damage done by heavy steam vehicles.

A Parliamentary Select Committee was set up to try and look at how public service vehicles could be used on ‘common roads’.

As part of this enquiry the Committee visited a tramway on which a steam locomotive had been running.

This was the North Metropolitan Tramway Company’s system between Stratford and Leytonstone, and the machine shown was ‘the well-known Merryweather steam tram engine …. many of which type have been working the regular traffic on lines in Paris for several months past, and with the most satisfactory results’.

Mr. J. C. Merryweather and Mr. H. Merryweather were present to see ‘The run most successfully performed, though the capacity of the engine was severely tested’.

The committee were told about Merryweather’s contracts for ‘tramways at Barcelona and Cassel, which latter line is under the special patronage of His Imperial Highness the Crown Prince of Germany’.

In the same year that the enquiry took place Merryweather’s sold one tram to the National Rifle Association in Wimbledon. This was take participants to the site of the shooting competitions on specially laid track which would be removed at the end of the competition.

It would be interesting to know how these vehicles – assuming they were exporting the entire vehicle and not just the engine -went from Greenwich High Road to Brazil, or wherever.

Obviously they went by ship but leaving from a wharf on Deptford Creek seems unlikely as a ship which was going to cross the seas to South America would not really been able to get that high up the Creek.

So there must have been some transshipment process where such vehicles could be loaded onto ocean going ships.

There is said to be only one Merryweather tram still in existence. It dates from 1881 and and is in a transport museum in Utrecht.

Merryweather’s continued to make horse-drawn fire engines until the 1890s.

Reports of late 19th-century fires in the press have a great feeling of excitement as appliances from fire stations around the area come galloping up with heroic firemen waiting to jump off and start pumping water.

These days we have no idea who our firemen are or who command them In those days each local fire chief was well known and each one was a hero.

The head of the London Fire Brigade was a major figure.

The Fire Brigade Chief James Braidwood was killed in the 1861 fire in Tooley Street at London Bridge and thus became a national hero.

There is a plaque to him on the corner of Battle Bridge Lane and Tooley Street.

He was replaced by the romantic figure of Eyre Massey Shaw who – as I mentioned in my book on the Creek – is mentioned in the Gilbert and Sullivan opera, Iolanthe, and took a bow on the first night when he there was with a lady who was not his wife… and one day I will write about firefighter, the Duke of Sutherland.

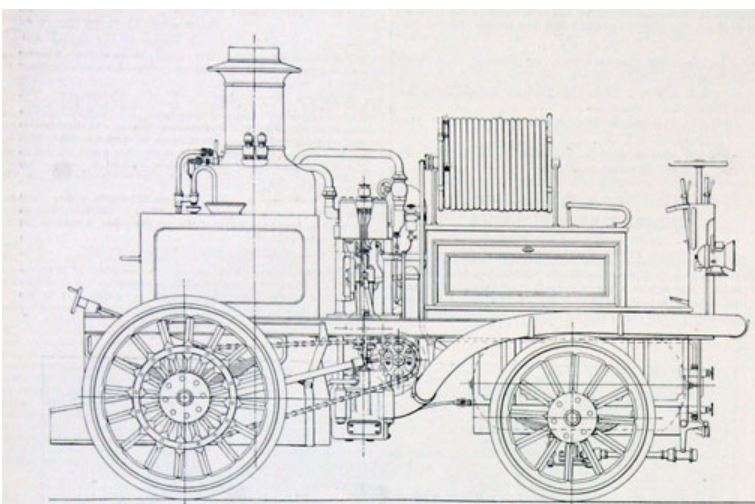

In 1899, Merryweather produced the world’s first ‘self-propelled steam fire engine’, the ‘Fire King’; which was for Port Louis on Mauritius.

By 1907 twenty-one Fire Kings were in operational use around the country, including one with the London Fire Brigade.

A modified Fire King was stationed at Whitefriars Fire Station in the City of London – it could go at a speed of 20-30 mph but was unable to negotiate a significant gradient without stopping to build up a head of steam

The first motorised fire engine in London was a Merryweather appliance delivered to the Finchley Fire Brigade in 1904.

It was commemorated in April 1974 by the issue of a 3.5 pence Royal Mail postage stamp.

The actual vehicle is preserved in the Science Museum store at Wroughton in Wiltshire.

It was fitted with a Hatfield petrol pump, which was the first fire pump powered by a petrol engine and capable of delivering 250 gallons per minute.

I am not sure if the fire float Massey Shaw counts as a vehicle in terms of this article – which is about road transport in the 19th century.

Massey Shaw was constructed by boatbuilders in the 1930s and she has even engines.

However she is associated with Merryweather for her pumps which have thrown river water up to great heights in a decorative way whenever her crew wanted to celebrate something.

She had an important role with a long history of attending fires in the River Thames both in wartime and peace.

She is well known for her her role in the Dunkirk landings and led the flottils of small boats back up the Thames to the London Fire Brigade jetty.

One oddity at Merrywearhes was their manufacture of what has been called the ‘first car’. I

n 1888 they built the Butler Petrol Cycle – a three-wheeled petrol vehicle. Edward Butler had been investigating a number of similar projects and had worked for a number of local firms – but not for Merryweather.

In 1887 he had patented a petrol driven tricycle and placed an order with Merryweather to manufacture a prototype, which they duly did.

Tests on it were not particularly successful and it appeared that its use would have contravened the ‘red flag’ acts.

Butler went on to other researches with other firms and manufacturers.

I have a long and detailed article about Butler by L.R.Higgins, which I understand is deposited in the Bexley archives.