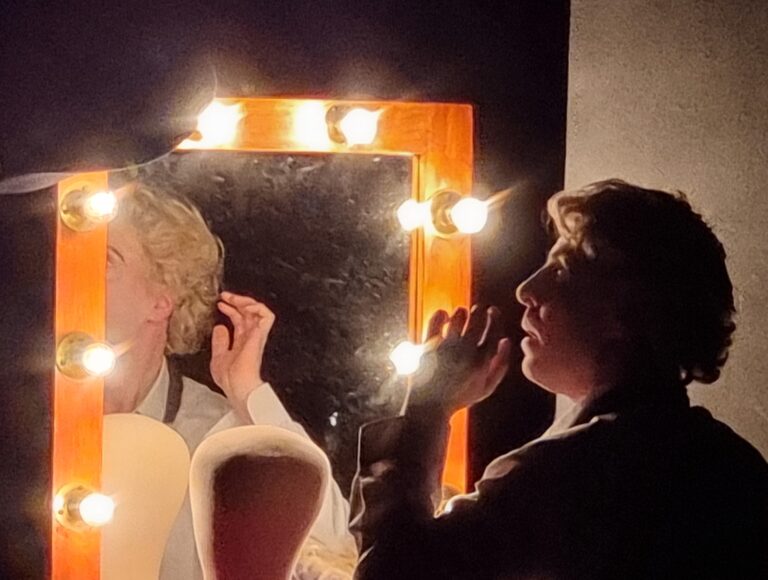

The first thing to say about Phaedra, just opened at the National Theatre, is that it is not an adaptation of the Greek myth, per se, writes Katie Kelly…

The writer and director have done more than drag the story into the present with, for example, combat fatigues, concrete or some hip-hop thrown in. This is a complete rewrite, a story inspired by the ancient original and subsequent interpretations. The closest it got to obeying the ‘rules’ of Greek tragedy was the ‘unity of place’ in the form of a cube within which all the action happened, though its contents were dramatically different between necessitating unusually lengthy pauses in the action, whose accompanying music and dialogue were served to build both story and tension.

The central figure in this play is Helen, in a nod at least to Greek myth. High-flying politician and paid-up member of what our Home Secretary would describe as the ‘wokerati’; she undergoes a steamy mid-life sexual awakening, but at what cost?

At curtain up, Helen, her husband, teenage son and adult daughter are preparing to welcome a mystery guest and anticipation is building. They are joined by Eric, the mild-mannered son-in-law.

In the original play, Phaedra falls for her stepson and there is a hint that Eric might be stepping into these shoes, but it is misleading, though he does seem more popular with the whole family than his wife, daughter Isolde.

The opening scene seems more like a Noel Coward comedy of manners than tragedy. The family energetically and entertainingly inhabit social stereotypes, but from the entrance of the mystery dinner guest, there is a palpable rise in nervousness.

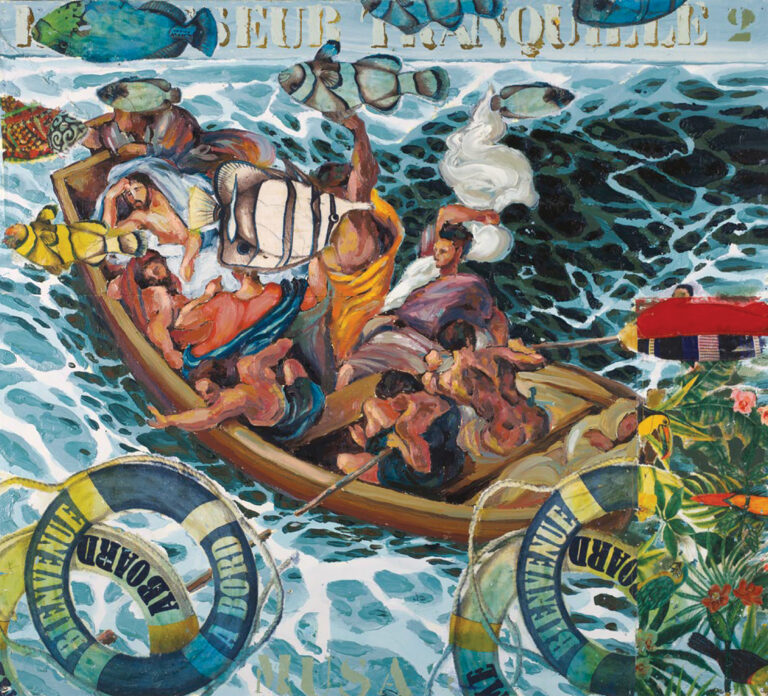

Sofiane is the son of Helen’s long-lost and ongoingly mourned Moroccan lover. A liaison that stemmed from a trip by her group of privileged Oxbridge buddies to taste local culture in more than one way, with catastrophic results.

Sofiane is disarming and charms both mother and daughter.

What is his reason for searching them out? Curiosity? Revenge? Does he even know himself?

There are many comic moments in what ensues but true to form, disaster is inevitable, inexorable and, if I am honest, slightly overplayed in the final scene.

All the acting is excellent, dialogue naturalistic and the staging impressive.

There is an enjoyable performance from Akiya Henry as Helen’s challenging friend. Assaad Bouab is extremely charismatic as Sofiane, convincing in his relationships with both mother and daughter and in his ultimate terrible unravelling.

A gripping and sophisticated offering from writer-director Simon Stone.

National Theatre, South Bank, London, SE1 9PX until April 8th. Times: Mon-Sat 7.30pm. Wed & Sat matinees 2.30pm. Admission: £20 – £89.

Booking: www.nationaltheatre.org.uk