Due to the sheer depth of the works of Shakespeare, the amount of adaptations and new works that have been inspired by them are innumerable. Now, Gary Owen’s new play Romeo and Julie, in a co-production with Sherman Theatre, has a run at the National Theatre on its Dorfman stage, writes Christopher Peacock…

Apart from the names, there is very little that feels borrowed from its near-namesake.

This is a teen romance but this time set in a poor working-class area of south Cardiff. The closest to star-crossed these two lovers come is that Julie is studying theoretical physics. She is a college student with dreams of studying at Cambridge, her Romeo, or Romy for short, has no such aspirations. A single father with an alcoholic mother, surviving and trying his best for his child is all this man-child can muster on a day-to-day basis. Although aged 18, as often mentioned by his mother, Barb, he is just a boy.

Performances from the whole cast are strong, Catrin Aaron’s drunk acting as Barb is handled with care and her subtle physicality prevents her performance from slipping into parody. Col and Kath, as Julie’s parents, don’t really get a look in during the first act with limited opportunity to flesh out the characters. They are working-class grafters, doing all they can for their daughter, placing all their hopes of climbing the social economic ladder solely on the route of their daughter’s education.

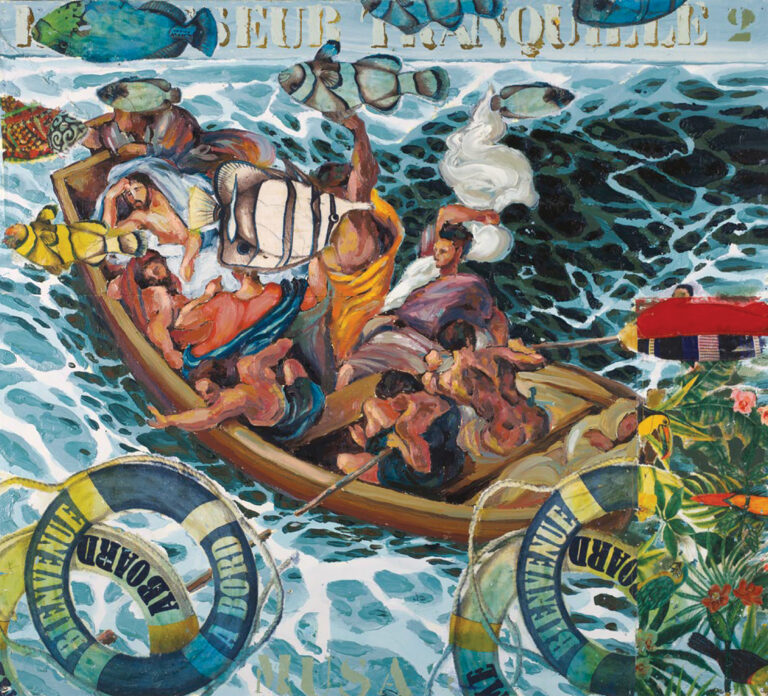

Hayley Grindle’s bare set design is adorned with neon lights of a variety of shapes that loom over the stage and are used to accent emotion and change. The ever-present cast on stage and moments of choreographed contact improvisation between scenes have a strong fringe theatre vibe, though neither greatly supports nor enhances the piece.

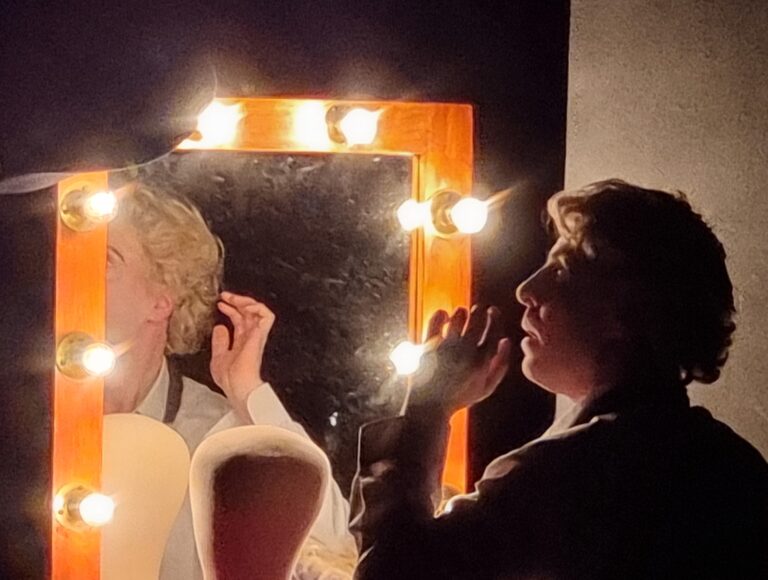

All young love is mired in complications and strife. Unfortunately, however charming Callum Scott Howells and Rosie Sheehy are in the titular roles, the stakes at risk fall short of dramatic. The tragedy is missing and the tensions between the two families represented are nearly non-existent apart from the odd line of dialogue. A lot of what is presented is rather predictable.

Owen’s want for the show to be a social commentary on the lives of working-class people comes across a little one-dimensional. An impassioned speech about the value of work and the oppression of the working class by their paymasters tries to get us into some meaningful content but does not captivate. His writing does succeed in encapsulating the humour of the working-class and bravado of young teens, many witty put-downs and jibes get laughs. This tale of young love does not match the tragedy of the work that it is supposedly inspired by and lacks as an exploration of working-class lives.

National Theatre, South Bank, London SE1 9PX until April 1st. Times: Mon-Sat 7.30pm; Wed & Sat matinees 2.30pm. Admission: £20 – £60.

Booking: www.nationaltheatre.org.uk