A wedding, the total destruction of a family; some would say it is the same thing. It certainly is in the case of Beth Steel’s Till The Stars Come Down, writes Bella Christy.

The core narrative explores the family’s relationships, but there is also a political undercurrent. Miners’ strikes, eastern European immigration, unemployment, and the cost of living crisis influence the heart of this piece. Given that we often grapple with political discussions in our own families, it adds a meaningful layer to explore this dynamic on stage.

Taking place in a de-industrialised town, the production focuses on the lives of a somewhat dysfunctional, working-class family as they navigate a wedding. Staged in the round, a more intimate staging than the traditional proscenium arch, I was drawn into the action, like I were an unassuming guest at said wedding, perhaps the distant cousin invited out of courtesy.

Surrounded by the audience on all sides, the family chaos was an almost immersive spectacle. Characters talking over one another, children darting around, and the blend of love and tension enveloped me into this authentic family dynamic.

The play opens with the women getting ready for the imminent wedding. Slightly larger than life characterisation comforts me. I watch the women of the family engaging in the familiar dance of bickering, laughter, and love — unfolding in a perfectly choreographed mess as they do each others hair, eat crumpets, and drink bucks fizz. A quintessential portrayal of girlhood. Some cliché stereotypes rear their heads: a wedding dress not fitting, warring relatives, wedding day jitters, and yet the play still feels so fresh.

I think every woman in that audience could find something about these women relatable. Whether it be remembering what it’s like to be 14, the unique love felt for siblings, or stressing about if you should curl or straighten your hair, there was something to identify with.

I initially found the bride, Sylvia (Sinead Matthews) to be unvaried, or perhaps plain, the weakest of the three sisters. But I was proved very wrong, and she surely became my favourite, and certainly the least bigoted. A brave innocence was portrayed expertly by Sinead. Although, actually, can I describe her character as innocent, having watched a rather gritty, spirited sex scene unfold? There is nothing like watching a sex scene while sitting next to strangers.

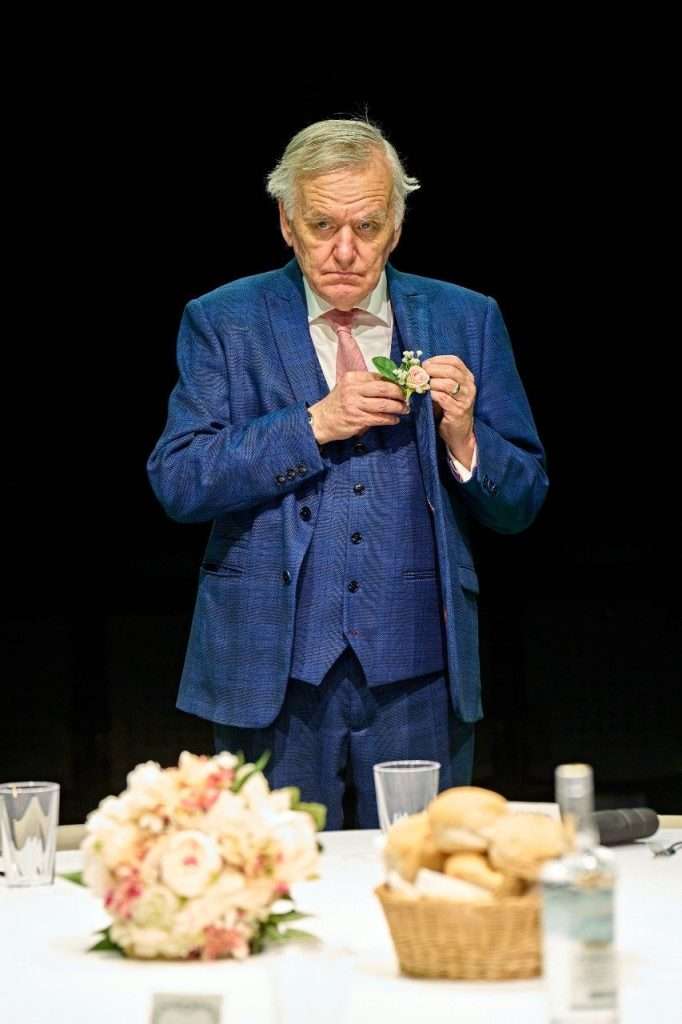

Having been an initial offstage presence, the men enter, and the dynamics of the family are fleshed out further. Tony, father of the bride (Allan Williams), had a withdrawn, grumpy personality as the play began — that quiet, man of the house persona. Though, as his own history unfolds we see glimmers of a much more complex character. His story feels like one that could have a telling of its own.

The rain falling (another wedding day cliche) carries particular significance: the undoing of the day. The second half of the play then shifts to mainly duologues and triologues, honing in on individual relationships and scrutinising ties between the characters. I liked this shift in form, it kept the piece moving forward in a stimulating way.

Without spoiling anything, the last 10 minutes I had my hands by my mouth, and the last 3 minutes my heart was clenching and tears were flowing. Brilliant.

You should watch this play, unless perhaps, you are getting married soon. as the woman sat behind me was…

National Theatre, Dorfman, South Bank. SE1 9PX until March 16th. Times: Mon – Sat Varied, Wd & Sat matinee 2.30pm.

Booking: www.nationaltheatre.org.uk